January 15, 2026

For more than 70 years, the Houston family has collaborated with the Canadian Inuit, committed to helping the world appreciate Inuit art and culture.

Arctic filmmaker, art dealer, and cultural guide John Houston is the latest force carrying that legacy forward. His work offers a rare, deeply human look into life in the Canadian North.

“My parents witnessed colonizers treating Inuit with Tapasunniq (to tease or belittle someone), yet they also recognized the brilliance and depth of Inuit creativity,” he said. Adding that his parents devoted their lives to shifting that perspective and to inspire the kind of astonishment that leads to genuine respect.

John Houston (left), Kenojuak Ashevak CC ONu RCA (1924–2013) (centre), and John’s wife, Ree Brennin Houston (right).

Growing up in Kinngait, Cape Dorset, John watched master carvers and printmakers call worlds into being. He remembers sitting behind renowned Inuk sculptor Osuitok Ipeelee as he carved a snowy owl from stone, while John tried to shape a small seal from a shard of serpentine the master had given him.

“In the late 1950s, I watched the first printmakers of Kinngait create what would become iconic works. At the time, Inuit intellectual culture wasn’t spoken about openly. Missionaries had suppressed drum dancing, throat singing, and ancient stories, but the art kept those traditions alive.”

Although John grew up surrounded by Inuit art, it took him years to understand how formative it was. When his family moved to England at age eight, he casually asked classmates what kind of art their parents made. His question was met with blank stares. Only then did he realize how rare his upbringing was, and how privileged he’d been to grow up immersed in Inuit culture.

“My parents often spoke of Tapairniq, the Inuit idea of being struck with sudden respect or awe for someone you may have underestimated.”

John Houston on board with Adventure Canada, cradling the sculpture “First Caribou,” 1948, by the late Conlucy Nayoumealook (1891 - 1958) of Inukjuak, Nunavik. (Credit: Dennis Minty)

At eighteen, when John returned to the North to work on the film adaptation of his father’s novel The White Dawn, he realized he had lost his Inuktitut. He kept meeting Elders and childhood friends, yet they no longer shared a language. That loss pushed him to relearn it.

He admitted that his parents cast long shadows. Everything he loved—art, storytelling, the Arctic—his parents had already done, and on a grand scale.

“I tried studying linguistics and psychology, but those paths weren’t mine. The breakthrough came when I stopped avoiding my parents’ footsteps and followed what truly excited me: graphic arts and filmmaking.”

After graduating from Yale at twenty, he knew he needed to return. He spent five years in Pangnirtung managing four annual print collections and regaining his fluency in Inuktitut. He later worked in film for many years before daring to make his own. At forty-five, he completed Songs in Stone, a tribute to his mother, to the artists of Kinngait, and to the extraordinary collaboration that brought Inuit art to the world.

The film taught him something essential: he could never make a film the way his father did, and his father could never make a film the way he does.

“That realization freed me to carry this work forward in my own voice.”

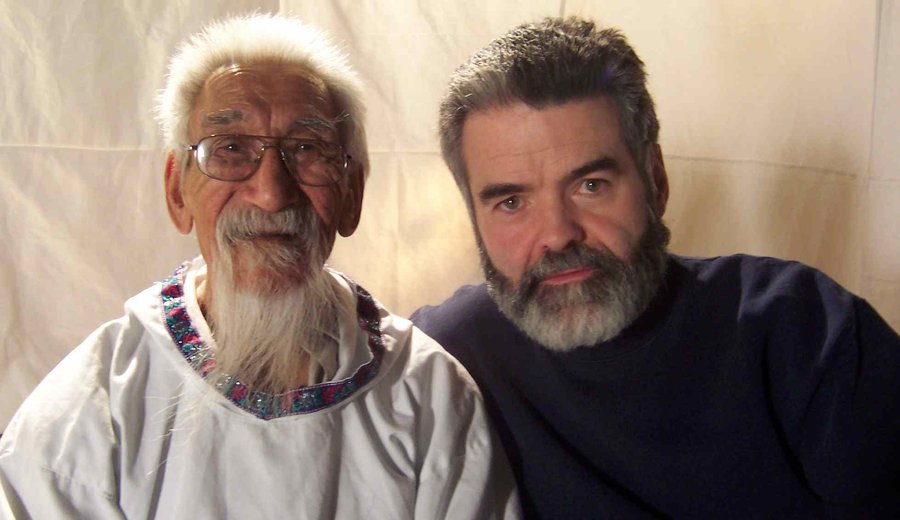

John Houston with Elder Samson Quinangnaq (1934 - D) was one of the primary informants for my fourth film, “Kiviuq,” and ended up acting in the film.

Even as a child, he sensed the power of art. Through films like Diet of Souls and Atautsikut: Leaving None Behind, he captures Northern life with deep respect and insider insight.

“In the recreation hall my father helped design, I remember watching my community watch a Western movie projected on a bedsheet. Their complete absorption made me want to create films of my own—films I would bring back to the North.”

Over time, John has come to understand his role less as storyteller and more as conductor.

“Inuit Elders, artists, and knowledge holders carry the stories,” he said, adding that his task is to provide the microphone, the spotlight, and the care required for those stories to be told faithfully.

According to John, he makes these films because he wants young Inuit to have access to knowledge that was withheld from their grandparents and parents for a century.

“For me, that work is the highest and best use of my time.”

Beyond filmmaking, he has spent decades supporting Inuit carvers and preserving traditions through ethically sourced artwork. As a cultural guide with Adventure Canada, he brings the Arctic to life for travellers, turning every encounter into an opportunity for learning, connection, and cultural exchange.

According to John, Inuit may not hold vast wealth, but they have something the world urgently needs: knowledge and Wisdom about non-confrontational conflict resolution as well as how to walk the earth without destroying it.

“When the world is ready to listen, Inuit knowledge will help us survive.”

John Houston giving a talk on board the Adventure Canada ship in October 2024. He is captured in his late father’s shadow, which he deemed “quite appropriate.” (Credit: Jeff Thomason)

He follows in the path set by his parents— his father, James Houston, who introduced printmaking to Inuit in 1957 and helped establish early standards, including strict quality control, limited editions, and fair payment. His mother helped create Canadian Arctic Producers, an Inuit-owned distribution system that still supports artists today. These structures enabled Inuit artists to develop distinctive styles now celebrated worldwide.

“My mother taught me the flip test: whenever you see questionable treatment of an Indigenous artist, flip the situation, would the same offer be made to a well-known non-Indigenous artist?” adding that this process “exposes the colonial assumptions beneath seemingly reasonable decisions.”

In his daily life, John practices reconciliation through his transparent partnership with sculptor Manasie Akpaliapik. Manasie creates what moves him, and John represents his work on equal footing.

“Together, we sink or swim. So far, we’re swimming.”

That same commitment guides his work with Adventure Canada, where he emphasizes that it is Inuit, not him, who truly helps travellers experience the Arctic through Inuit eyes. He is proud to have brought the first Inuk on board, and many more since, while securing funding to train the first generation of onboard cultural educators.

For information on John Houston and the Houston North Gallery visit https://www.houston-north-gallery.ns.ca/

Banner Image caption: John Houston in Adventure Canada role outside in his “truly happy places” (Credit: Jeff Thomason)