Arctic fieldwork can be physically and mentally demanding. Even with the luxury of driving a truck to field sites can leave you tired; being exposed to the elements on an ATV has the potential to sap all the warmth and energy from your limbs by the end of the day.

I began my career in 2017 as a Research Technician in Manitoba’s subarctic at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. After two contracts there, I began traveling to Nunavut as a graduate student funded by Polar Knowledge Canada, a federal agency.

All my Northern summer field seasons have left me tired and ready for a break. Despite the sometimes grueling conditions - for me, a Southern gal, the Arctic pulls me and many of my colleagues back year after year. It’s a world unto its own; the landscape seems empty and hostile at first glance. Once you look closer, you will see that it is brimming with life.

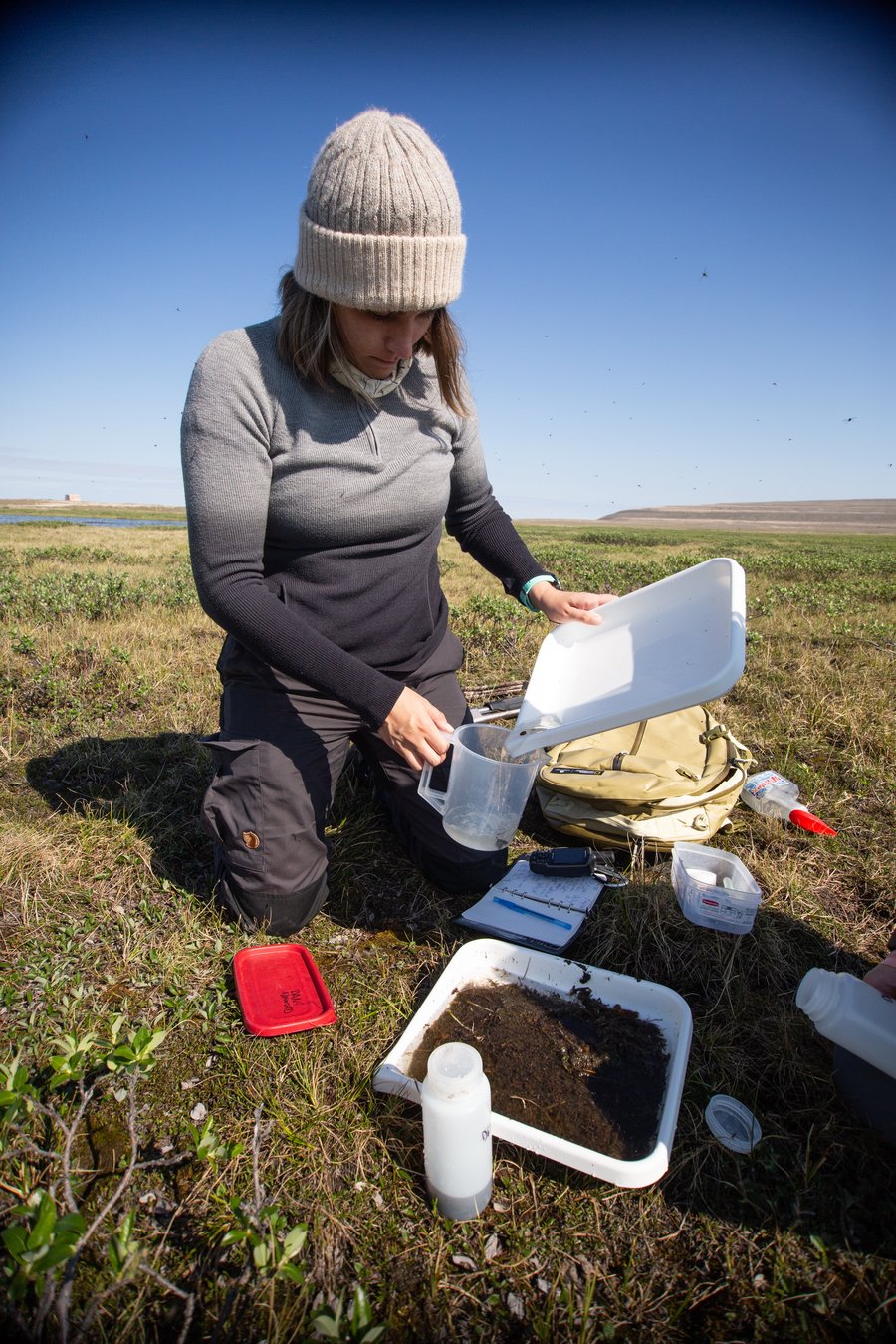

Collecting freshwater invertebrate DNA on Kitlineq

The summer of 2021 marked my fourth field season in Canada’s North and my second in Iqaluktuuttiaq, Kitlineq, Nunavut (Cambridge Bay, Victoria Island). All of my sampling takes place on Inuinnait Nuna, the Inuit homelands in the Kitikmeot region.

The plan was to collect freshwater invertebrates from as many habitats as possible and contribute to a project called Arctic BIOSCAN (ARCBIO). ARCBIO is a 7-year project being spearheaded by the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics (CBG) at the University of Guelph that aims to create a DNA-based sequence library of all Arctic life.

My role within this project was to contribute freshwater invertebrate data so that we could build up the DNA reference library on the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD), the online genomic repository created and maintained by CBG.

There was no freshwater invertebrate biodiversity baseline on Kitlineq at the time – DNA or otherwise - and I was looking to fill in that gap. Despite the wrench that the COVID-19 pandemic threw into all the ARCBIO plans, I managed to get back to Iqaluktuuttiaq for five weeks.

Preparing for a canoe-based expedition

Our team consists of Elise Imbeau and Gabriel Ferland, owners and operators of Viventem, a scientific support company, and a young local, Carter Lear.

I was starting to feel down about the lack of geographical range I was getting for sampling sites. Accessibility is limited and I avoid driving ATVs off-road as they cause permanent damage when the tires tear up the tundra.

There were plans for several helicopter trips but none of them worked out, mostly due to weather.

As the end of the field season loomed closer, loose plans for a backcountry canoe trip with Gab and Eli seemed like they were falling apart, especially since Gab was out of town. Flexibility, resilience, and adaptability are vital to planning the logistics of remote fieldwork.

When Gab returned less than a week out from the proposed expedition, he immediately began scouting out potential routes by checking maps and satellite images. The end of the season presents difficulties when it comes to traversing the landscape in canoes because many water systems dry up, either partially or entirely, over the summer months. Without current satellite images, planning for the trip involved a fair bit of guesswork.

In addition, we were attempting a route that isn’t usually taken, making this trip largely exploratory in terms of science and the route itself.

After deciding which path we would take, my enthusiasm spiked. Gab and Eli would plan the logistics while I thought more about how many and which types of samples I wanted to collect, and Carter agreed to tag along and assist. His efforts and expert local knowledge were a welcomed addition.

It was a treat to be working with such seasoned professionals with extensive backcountry experience and knowledge of the area.

Danielle Nowosad collecting samples for the Arctic BIOSCAN project. (Photo: Danielle Nowosad)

Day 1

Launch day arrived and I was up at 6 a.m. buzzing around to ensure that I had all my sampling equipment. I sat with Gab and Eli’s 90 lb plus Malamute/Lab mix, Shila, on my lap as we bumped along a well-worn gravel road in a pick-up truck.

As the dog’s weight forced my face to press uncomfortably into the frame of the truck, thoughts of doubt started passing through my mind. I had been sitting in my home office for a year and a half with minimal exercise, not to mention the three traumatic brain and whiplash injuries I obtained in the last two years. Unbidden, my mind started listing all the injuries that might prevent me from functioning on an expedition that relied on my body’s ability to carry me through.

My thoughts were interrupted by a sudden yell of surprise. There were two muskoxen on the side of the road! Nobody had seen them this close to town for over twelve years., My fears melted away and were replaced by renewed excitement.

The truck disappeared quickly, leaving us with hundreds of pounds of gear, two canoes, four humans and one Shila in the shadows of the largest glacial esker in the area (Uvayuq/Mount Pelly).

I grabbed my paddle and gracelessly stumbled into the front of a canoe. With Gab in the back and Shila perched on top of huge bags, our canoe was sitting low in the water.

Kingmitquq (First Lake in English) went by quickly. We took water quality measurements using an instrument called a YSI, benthic invertebrate samples on the shores of islands using a D-ring dipnet, and zooplankton samples with big nets off the side of the canoe in deeper water.

You’re committed now, Dani!

The regular stops for sampling gave my aching muscles desperately needed respite. Gab and Eli are expert paddlers and were always ready to facilitate any sampling. Carter handled taking invertebrate samples with various nets while I labeled sample containers and wrote notes in my field book about location, water characteristics, and YSI values.

We made it out of Kingmitquq and into the transition zone leading into Qiluguq (Second Lake). We make it through Qiluguq without incident and pull the canoes up on shore, emptying all the gear and steeling ourselves for the first portage.

The gear is in large, awkward bags not designed to comfortably carry for distance. One kilometer into the portage I put my bag down and lay down on the tundra to catch my breath. The portage was two kilometers total, covering fens, rocks, hummocks, and hills.

It took us nearly two hours to portage the gear and both canoes to the northern edge of Long Lake and by the time we dropped the last pack, we were closing in on 6 p.m. Gab handled the heaviest packs and carried the canoes single-handedly.

We hadn’t made it to the first scheduled camping spot but decided that between the dipping air temperatures and general energy levels in the group, it would be best to stop for the night and build our camp. Gab and Eli quickly constructed a kitchen and clothes drying rack using the canoes as windbreaks and the paddles as poles to drape a tarp on.

At the same time, Carter and I shivered through processing the invertebrate samples we had collected that day by picking out specimens and preserving them in ethanol. For the first time, it dawned on me that it was not possible to start a campfire for cooking or warming up – we were well above the treeline.

I opened my pack to search for another thermal layer to discover that all my clothes were sopping wet. The wet clothes I was wearing combined with the temperature dropping to nearly 0 degrees Celsius made me frustrated beyond belief.

We hung all our wet gear out to dry hoping the strong winds would pull the moisture out of the fabric. That “night” (we were still at nearly 24-hour daylight at this time of the year), I crawled stiffly into the tent, wriggled gratefully into my ultra-warm sleeping bag, pulled my buff up to my nose and my toque low over my eyes, and slowly drifted into a deep sleep – comforted by the knowledge that Shila was keeping watch for bears and wolves outside. .

Shila monitors the shoreline while the research team paddles down the planned route. (Photo: Danielle Nowosad)

Day 2

The second day began with the four of us sitting puffy-faced (me especially) and sore behind the makeshift lean-to, trying to eat peanut butter toast and drink coffee before it rapidly lost warmth.

Luckily, my warmest gear managed to dry out overnight! Eli and Gab offered to start packing up our camp while Carter and I did some sampling nearby.

Being the star bear guard she is, Shila trotted back and forth between both groups, often sitting down exactly halfway between both to ensure she could keep an eye on all of us. We finally set out on Long Lake around 11 a.m. My sore body quickly warmed up as I fell into a rhythm of paddling.

I was dreading the second portage. We pulled the canoes onto shore on the west side of Long Lake and I looked despairingly up the steep hill that ascended from the prows of our canoes.

Almost immediately after landing, Carter spots some balloon-like reproductive structures on an uncommon type of moss that was pointed out to us by a botanist earlier in the season. A second later, I find some biological soil crust that I was on the hunt for – just enough excitement to cut through my apprehension for the upcoming portage.

Although this portage was relatively short, I was huffing and sweaty by the time I made it to the next lake. Eli and Gab, the incredible super-human troopers that they are, handled transporting the heaviest gear while Carter and I ran off to take more samples in little ponds nearby.

Despite the physical exertions and non-ideal weather conditions, morale stayed high as we paddled through beautiful crystal-clear water systems. The plankton nets drift through the water like pale ghosts, including one that unfortunately unclipped from its rope and faded into the emerald depths.

By the third portage at 7 p.m. I was starting to lose steam. A qugjuk/tundra swan slowly drifted away from us as we touched down at the western edge of yet another small lake. Thankfully, this portage was short enough that we could see the edge of the next lake.

Gab and Eli quickly patched together a plan of action: we would all carry something heavy on the first trip, then Carter and I would set up a tent so that we could process a large number of samples as they once again offered to do the heavy lifting (literally). The weather took a turn towards rainy and temperatures remained low, Eli must have known I wouldn’t have lasted long if we had attempted to process the samples outside again.

The importance of having such experienced, competent guides to facilitate the trip struck me once again as Carter and I emerged from the sample processing tent and Eli told us that both the main and backup cooking stoves had broken, but Gab had worked for more than 30 minutes to fix them. There was no panicking, just rational and level-headed problem-solving. We all sat cross-legged in the second tent enjoying a piping hot meal with muskoxen meat that Gab and Eli had hunted themselves while Shila made herself a little bed just outside the entrance. That night, Eli and I once again settled into our sleeping bags, loaded shotgun between us, and dropped into a hard-earned sleep.

The research team consists of Danielle Nowosad, Elise Imbeau and Gabriel Ferland and Carter Lear. (Photo: Danielle Nowosad)

Day 3

We were all awake by 7:30 a.m. The stove cut out again after we each had one piece of peanut butter toast and I thanked my lucky stars that the coffee had been made earlier. The weather seemed to be looking up for today; even just a few extra degrees Celsius is noticeable when you’re in Arctic conditions.

We were eager and unsure as we ventured into the part of the trip where we were unable to predict the water levels in the river. We quickly packed down the camp. Our movements were now practiced and sure as we launched onto the last large lake of the expedition. Shortly after stopping for a dipnet sample on the shore of the lake, I noticed three tuullik/Yellow-billed loons calling to each other nearby.

One, two, three samples were collected as we reached a shallow stream flowing out of the lake. The canoes beached in shallow water, I hear Eli yelling from shore several hundred meters away as I set up a passive zooplankton net. By the time I was finished, she and Carter had caught three enormous iguttaq/bumble bees whose DNA would eventually contribute to ARCBIO. The stream was shallow enough that the canoes could be pulled along like enormous, reluctant dogs on a leash and I was grateful to avoid another portage.

We finally ran out of luck with water depth and we pushed, pulled, and prodded the canoes along in the shallow stream bed. Gab handled guiding the canoe along, aiming it towards slightly deeper water to avoid pulling it over large rocks that might cause damage. This method is significantly easier than unloading all the gear and portaging.

We were heading into the final stretch of the trip with more than 30 kilometers of distance traveled behind us. Another unknown stretch was coming up after the final small lake – would there be enough water to paddle in the stream all the way down to the higjaq/Arctic Ocean shore?

Too quickly, large rocks and shallow water depths prevented us from paddling any further and my daydream of triumphantly shooting down a swift-current river into the ocean was not possible. I looked apprehensively at the distance before us and was slightly heartened to see the ocean in the distance.

It was easy to sense the fatigue settling over the group, although Gab and Eli maintained their previous exertion levels and positivity. We heaved the largest bags onto our backs and carried them downhill to the beach and waited to see if our scheduled ride home was nearby.

My energy stores were dwindling quickly and I was starting to feel impatient about our extraction. With the sun finally out and low winds, the mosquitoes made their presence known by swarming any exposed skin. I breathed a sigh of relief as I saw Gab haul the blue canoe the last few meters and realized I would not have to carry heavy gear across challenging terrain any longer.

Reflections

We consider the canoe expedition a success. With more than 40 kilometers paddled and walked, we collected 28 freshwater invertebrate samples and several YSI readings that I and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans will make use of.

In my 5-week field season, I collected a total of 105 samples, so 28 in just three days is impressive. This trip has shown me how incredibly useful canoeing is to scientific research - something Gab and Eli have advocated for for years.

Many researchers opt for ATVs, which have limited access to different areas, especially water, or helicopters, which use a lot of fuel and tend to be very expensive. Helicopters are also highly weather dependent, whereas canoe trips don’t require perfect conditions. Using canoes, we can study entire watersheds and observe systems with our boots on the ground.

This trip was so successful because Gab and Eli were expert guides and went into the expedition prepared for every possible safety situation. They packed antihistamines even though none of us had a history of allergies. We had two loaded firearms, and always moved in groups of two or more to ensure we were prepared for any interactions with bears or wolves, in addition to always having Shila the bear guard dog with us.

We had a satellite phone that Gab would use to update the home base back in town every night to send them our coordinates and let them know we were doing fine. We had extra battery packs safely stored in a waterproof Pelican case, and even if that and all our other electronics failed, there were backups to ensure we could navigate our way to the extraction point. There was enough food to last us two extra days, an extra stove, extra fuel, and a loaded first aid kit. The list goes on - every measure was taken to minimize risks.

The entire experience was difficult but overwhelmingly positive. I am completely convinced of the merits of canoe sampling and began writing grant applications to support similar trips.

This canoe trip was funded and supported logistically by the Arctic BIOSCAN project and Polar Knowledge Canada. Traditional Inuinnaqtun names for places are from inuitplaces.org.

Dani Nowosad is working towards a PhD at the University of Guelph. Find her on Instagram @danimanitoba, Threads @danimanitoba, or contact by email at [email protected].