Nearly all of the Arctic region’s development challenges can be tied to one issue: the striking lack of transportation options.

Canada’s Arctic north, spread over the territories of Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon, are all substantially less wealthy than the southern provinces. One of the biggest reasons for this wealth disparity lies in the difficulty in transporting goods to a region which is sparsely populated and has few highways and rail links.

The impact of these transport deficiencies is apparent in the costs of trade between northern territories and southern provinces. Trade costs are 45 per cent higher over similar distances, largely due to poor transport infrastructure. Shipping distances average over 2,100 kilometers, compared to the average 1,400 kilometers for trade within provinces, according to a 2018 University of Calgary study.

This results in a shortage in construction building materials, urgently needed in territories where thousands live in inadequate housing. In a 2023 Government of Canada study on housing in the northern territories, 9.9% of residents of Yukon, 11.4% in the NWT, and 40.5% in Nunavut are classified as “in core housing need,” which often means overcrowding.

The majority of the Arctic territories’ transportation infrastructure are winter roads or “ice roads,” only accessible in the winter months. The months when these vital roads are serviceable are growing shorter, due to climate change which is making the roads less secure and able to support heavy cargo trucks. Other areas of the Arctic territories are served by ship, though these are only accessible during the short summer period when ice is no longer a barrier.

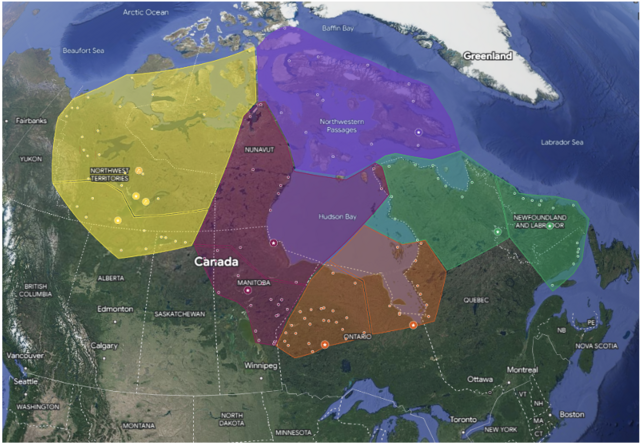

Canadian Arctic Innovation Association's report determined five corridors that would service the majority of residents in the territories. (Photo: Canadian Arctic Innovation Association)

Could airships solve the issue?

For some, airships – often referred to as “blimps” with a small passenger compartment and a massive, often-hydrogen-filled balloon – present the ultimate solution to solving the northern territories’ infrastructure gap and substantially bringing down the costs of transport and goods to the regions.

In May last year, a group called the Canadian Arctic Innovation Association, a group including First Nations and Inuit groups, transport experts, and activists for northern development, called on the Canadian government to formulate a clear policy statement on where they stand on airships to service northern territories and development of an airship pilot training system. It also called for a cold-weather testing facility to ensure that airships could withstand the frigid temperatures of its Arctic territories.

Their argument is that airships are economically more feasible than relying on airlines and expansion of railways and highways to provide cargo to Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. The group also emphasised that a multimodal method of transport – using airships to access areas where rail and highway did not reach – would be the most cost-effective away of transporting goods to the region.

The report determined five corridors that would service the majority of residents in the territories, while also enabling airship companies to remain economically solvent. These include: the North West Corridor, which would service Yellowknife and its environs; the Central West Corridor, to service Churchill, MB and Thompson, MB and their environs; the Central East Corridor, which would bring cargo to the Moosonee and Pickle Lake regions in Ontario; the North East Corridor, which would serve the Schefferville region in Quebec and Happy Valley region in Newfoundland and Labrador; and the North Arctic corridor, which would provide cargo to Iqaluit and the surrounding region.

“Most people know two things about airships: the Goodyear blimp and the Hindenburg.”

Barry Prentice, a longtime airship activist and Professor of Supply Management at the University of Manitoba, told Arctic Focus that airships are needed, and soon.

“It won’t be long before the ice roads aren’t working,” he said, pointing to the drastic impacts of climate change in Canada’s north.

“It’s in our collective interest as a society to do what we can to try and change the conditions there.”

As an economist, he links the region’s poverty to the lack of transport options, for cargo and individuals alike.

He also dismisses safety concerns about airships.

“Most people know two things about airships: the Goodyear blimp and the Hindenburg,” he said, referring to the airship disaster in 1937 which killed 35 on board after it caught fire during landing.

There were many more airships in circulation before Hindenburg (“129,” he said), and what ended airships’ popularity wasn’t the disaster but the advent of the jet liner.

“[Jet liners] were so economic and fast, that they put everything out of business – ocean liners, railways” and the airship industry.

“We can’t just keep dumping huge amounts of carbon into the atmosphere,” he said. “Everything you need to build an airship can be obtained in the airplane supply chain,” he added, reemphasising that the economic models presented in the report demonstrated that a solid business case exists in the northern territories.

Transport Action Canada, a citizen transportation advocacy group, also supports the development of airships as a response to the transport woes in the northern territories.

“We are very conscious of the need to get heavy lift into the Arctic for construction materials in a way that is affordable,” President Terry Johnson said, adding he didn’t understand why there seemed to be hesitation within the federal government on moving forward.

“Why is what is apparently a clear line of sight in sustainable logistics taking so long?”

But others remain skeptical that airships are a viable solution.

“People here want [goods] faster, and airships are not that fast,” Jim Wilson, Vice President of Operations at Inuit-owned consultancy Nunatta Environmental Services told Arctic Focus.

“Airships are good for heavy loads, and for places that aren’t in a big rush.”

Airlines are faster, but require more infrastructure: many northern airports do not have sufficient runways, including those in Iqaluit and Rankin Inlet, he said. Airlines have asked the federal government to upgrade runways and move away from the gravel runways currently seen at northern airports.

“There are applications where airships could be used and would work, but there are quite a few limitations in getting them to operate,” he said, pointing to winds of 80 kilometres per hour.

Airships would also need hangars to shield them from the elements to protect them from wind and cold damage, he said.

The Quebec government has invested C$77 million in the Flying Whales Group since 2019, and now owns 25% of the company. (Photo: Flying Whales)

Making it happen

One company, France-based Flying Whales, has made significant progress towards building airships and making them operational, CEO Arnaud Thiolouse told Arctic Focus.

“We passed in 2022 the preliminary design review of the airship – this is the review that validates design, based on the performance we set, and then we enter into a phase where different partners for different systems [for the airships] have their own tests, which began this year,” Thiolouse said.

Partners include Pratt & Whitney Canada, Thales Canada, and Delastek.

The company has a branch subsidiary in Quebec, which is now testing a 1-megawatt turbogenerator, based on a thermal turbine, Thiolouse added.

It has hired nearly 30 people in Quebec, while its parent company, based in the outskirts of Paris, employs approximately 200 people. The Quebec government has invested C$77 million in the Flying Whales Group since 2019, and now owns 25% of the company.

Flying Whales plans for three factories worldwide: a factory in France which will produce airships for the Europe and African markets, a Quebec factory which will produce airships for the Americas, and a third in Australia to service the Asia-Pacific region.

The company is targeting 2027 for first production from the Quebec factory, Thiolouse said. The company has narrowed down possible locations for the factory to three, and will decide this year where to break ground.

On the certification front, Flying Whales has been working very closely with Transport Canada, Thiolouse said.

Establishing baselines for certifications is incredibly important when manufacturing new products, he said.

“It would be extremely dangerous for airship manufacturers if you let the certification authority define regulations that aren’t based on a baseline,” he said.

“When we started [designing airships] it was a kind of a risk, and that’s why we started to work early with a liaison [at Transport Canada] to have the certification which fits this aircraft.”

The company is also working with Transport Canada on developing a scheme to certify airship pilots.

“We’ve been in talks with Transport Canada on airship pilot training programmes since the beginning of this year,” Thiolouse said. “We split off the operating company [a subsidiary called] Flying Whales Services. The goal for the Services branch is to handle the activities usually done by airport operators and airliners.”

Transport Canada, when reached for comment, would only say that the ministry maintains safety standards that would enable the certification and operation of airships in Canada.

As for routes expected to be used by the airships in Canada, Thiolouse said these are still in development.

“We will expand our fleet looking at the precise area where we can fly in a radius of 500 kilometres,” he said. “We’re looking to maximise the value we create in terms of loading and unloading and not taking up a lot of time, and then will work with our marketing and commercial teams to create good connections” with populations needing airship assistance.

“We want to work together in defining [the routes], and hiring locals to operate our airship,” he said.