ack in time, Inuit were once independent, and not subservient to others. Their greatest challenge in life was the pursuit of food and sustenance from their Arctic environment. This they did for millennia, by ways and means suited to the climate in which they lived. The Arctic’s seasons and resources ebbed and flowed in cycles of plenty and famine, with inherent hardships that often resulted in death by starvation. But Inuit survived and thrived in these cycles from time immemorial: Inuit were once secure, not in quotation marks, in their homeland!

When outsiders of whatever origin first came upon Inuit in their natural state, they discovered them to be living adequately in surroundings, which seemed quite impossible for human beings to conquer. To the first non-Inuit who encountered them, their existence appeared to be precarious. But had Inuit not succeeded in beating the odds of making a living in the Arctic, outsiders would not have had any Inuit to “discover”. Inuit had mastered their environment!

Inuit sovereignty in the Arctic started being systematically undermined long before there was regular, sustained contact with civilization. This is a brief story of the resulting decimation of Inuit security, which exists to this day...

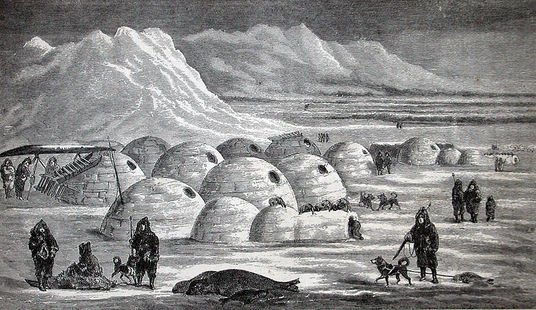

Inuit Village near Frobisher Bay (from C. Hall's Arctic Researches and Life Among the Esquimaux, 1865)

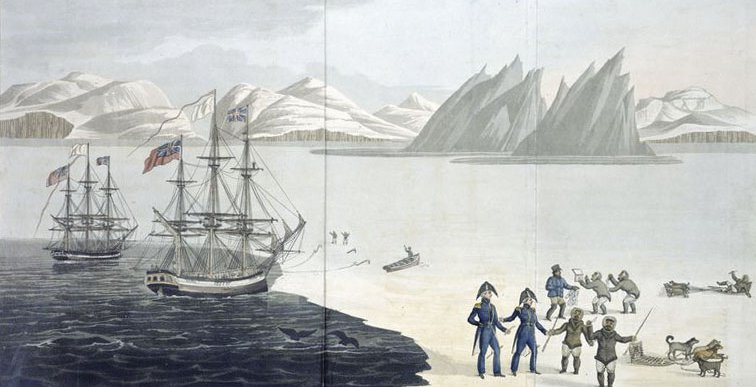

On June 8, 1576, three ships under the command of Martin Frobisher departed from England on a voyage that would reach southern Baffin Island. Queen Elizabeth I is said to have waved from a window to convey her good wishes to the expedition. It is certain that those good wishes did not include formal instructions to Frobisher to secure all relevant permissions and licenses from local Eskimos before proceeding with any mining venture on their lands.

This colonial “oversight”, we know, was no accident. The pattern of behavior of European monarchs and their successor governments would use such “oversights” down through the centuries to assault and decimate the security and well-being of indigenous people, including Inuit, the world over.

The British legal system, as used by its Monarchs and colonial/post-colonial governments, is the single most lethal weapon used to eradicate Inuit sovereignty over Arctic homelands in Canada. There’s no room in this system for indigenous oxygen. It was, and still is, utterly foreign to Aboriginal life. The system has built-in absolute superiority over lesser beings not descended from Europeans. No defense against it has ever been discovered, and its effects reign to this day.

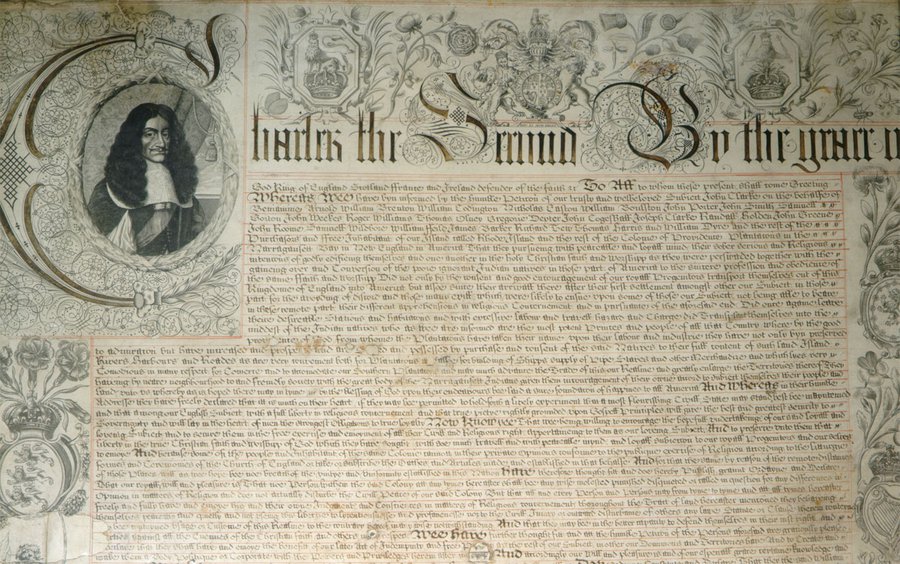

1670 royal charter of the “Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson Bay.” Source: Hudson’s Bay Company Archives

On May 2, 1670, King Charles II of England issued a royal charter to his cousin Prince Rupert, granting him title to vast areas of the future Canada. “Rupert’s Land” was established as the private domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company. A telling feature of this act was the King not even bothering to first claim “ownership” of these lands before signing them over to his cousin: The King believed that the land was his to give because no other Christian monarch had claimed it.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763, issued by King George III, might have been useful to define a more equitable relationship between the Crown and indigenous people. It established the constitutional framework for the negotiation of Indian treaties with the Aboriginal inhabitants of large sections of Canada. This document is even referred to in section 25 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982. But it has never resulted in a more equitable definition of securing a place for Aboriginal people in the country’s legal and constitutional structure.

Canada’s history is littered with land and real estate/jurisdictional transfers, made with total abandon by kings, queens, and later, post-colonial governments. After 200 years, the Rupert’s Land of King Charles II was transferred to the new Dominion of Canada, and transformed into the Northwest Territories in 1870. Such acts transpired without anybody considering what the original inhabitants of these territories might think of these arbitrary dealings.

For Inuit in Nunavik, the northern landmass of Quebec, such dealings included the transfer of Ungava District of the Northwest Territories to the Province of Quebec in 1912. My great-grandfather, Patsauraaluk, born prior to 1870, was first a citizen of Rupert’s Land. Then for most of his life, forty-two years to be exact, he was a citizen of the Northwest Territories. He died in the years after 1912, a citizen of Quebec; all without having moved anywhere!

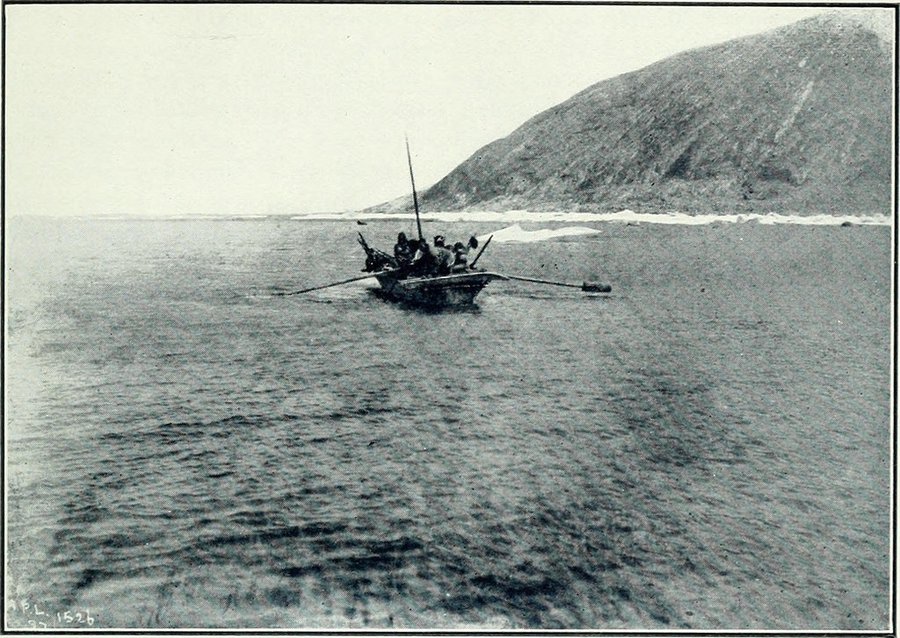

An umiak, a type of open skin boat used by the Inuit, in Ungava sometime in the early 20th century. Taken from "Extracts from reports on the district of Ungava, recently added to the province of Quebec under the name of the territory of New Quebec" (1915)

Post-colonial governments eagerly took over what had previously been the realm of kings and queens, in the application of legal brute force to change and determine the status of vast stretches of the Inuit homeland. One further arbitrary act was a legal decision, made in 1939 by the Supreme Court of Canada, called In Re: Eskimo. That decision, made without its subjects’ participation, declared that Inuit (Eskimos) in Quebec were “Indians” for purposes of legal definition.

Given this sort of history, it’s no wonder that governments have governed the Inuit homeland in ways that have required formal apologies for residential school abuses, forced relocations from traditional lands, and slaughter of sled dogs, the primary means of Inuit mobility. Inuit have been treated in many ways like “chattel”, as former Prime Minister John Diefenbaker once said.

Canada and its provinces and territories had an opportunity to correct and reset its relationship with Inuit and other Aboriginal people in the First Ministers’ Conferences on the Constitution in the mid-1980’s. The primary objective of those conferences was the search for the recognition of the Aboriginal peoples’ right to self- government within Canada. Unfortunately, attitudes borne from colonial history were still too strong among the governments of the land to facilitate the ungrudging recognition of such a right in Canada’s Constitution.

So the First Ministers’ Conferences failed, and inclusion of the rights of Aboriginal people remain as major unfinished business in Canada’s structure as a nation. Canada continues to exist on the perpetual fiction of being made up of “Two Founding Nations”, the English and the French. Until this deficiency is corrected, Canada will continue to be an incomplete nation, with its Aboriginal elements on the outside periphery of its nationhood.

Inuit have yet to find true security in Canada…

Zebedee Nungak was born at Saputiligait, his family’s traditional area forty miles south of Puvinituq, Northern Quebec. Mr. Nungak’s first stint in elective politics was as Secretary-Treasurer of the Northern Quebec Inuit Association in January 1972. Thereafter, he was a seasoned fixture in the Arctic political scene for close to three decades. He is an accomplished writer, having contributed numerous articles and commentaries to newspapers and magazines.