he Arctic Ocean is not only the smallest, shallowest and most northern ocean in the world, it is also experiencing some of the most dramatic effects of climate change and other environmental perturbations. Any attempt to manage such a complex system must simultaneously account for the global context and multiple local to global interactions between humans and nature. Not to mention possible unexpected abrupt changes, which can and have occurred as ecosystems in the Arctic lose resilience.

A study published in Ambio proposes a new framework to support management that builds on a social–ecological system perspective on the Arctic Ocean.

The study is part of an Ambio special issue on the European Union project Arctic Climate Change, Economy and Society (ACCESS).

The authors behind the study are Anne-Sophie Crépin, Åsa Gren, Gustav Engström and Daniel Ospina, from the centre and the Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics.

Their article illustrates the framework’s application for two policy-relevant climate change scenarios: a shift in zooplankton composition and a crab invasion.

Our holistic approach can help managers identify looming problems arising from complex system interactions and prioritise among problems and solutions, even when available data are limited.

Anne-Sophie Crépin, main author

Operationalizing the social-ecological approach

The researchers call their approach Integrated Ecosystem-Based Management (IEBM). It merges insights from Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) with a Social–Ecological System (SES) approach to support management during uncertainties about future development.

What this means is that while EBM focuses on the nature part of an ecosystem, IEBM focuses on sustainably managing both nature and humans together, as an integrated whole.

The SES approach in itself is about picturing a system where social and ecological patterns and processes interplay.

However, IEBM focuses more explicitly on management and “takes into account the crucial role of ecosystems to provide goods, services and other relevant activities that contribute directly or indirectly to human well-being and Arctic sustainable development,” the authors argue.

Climate, zooplankton and fish

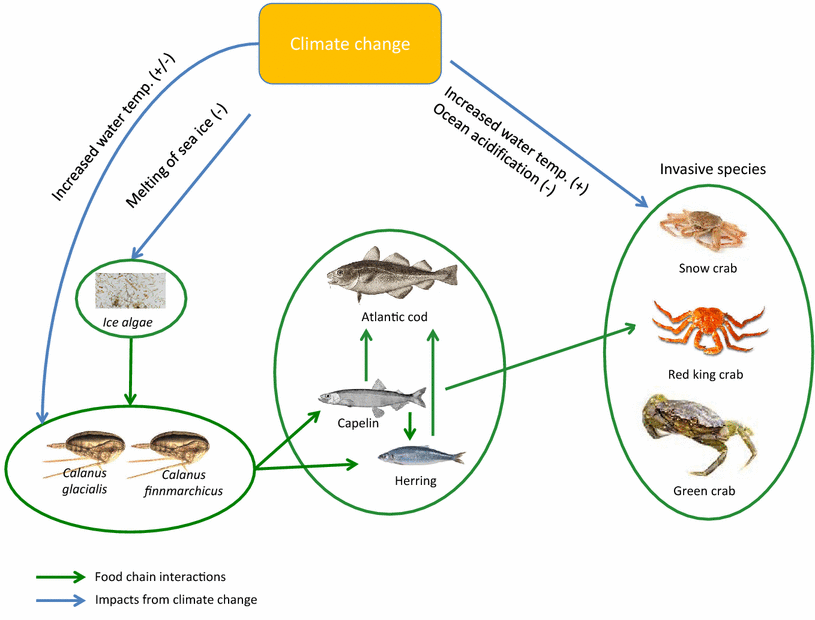

The authors identified six future scenarios, and focus more in detail on two of them. The first scenario focuses on how a warmer climate will likely favour the less fatty Calanus finmarchicus at the expense of the dominant zooplankton species Calanus glacialis. Such a shift could have negative impacts on the species that feed on zooplankton, like capelin. Not to mention the potential spin-off effects on herring and Atlantic cod, which in their turn prey on the capelins.

The second scenario in focus looks into a potential future where the introduced invasive species red king crab has grown to be of great economic importance in parts of the Arctic. Already today, the red king crabs supports a 26 million USD fishery in the Barents Sea, but at the same time the crabs have also been reported to impact bottom-dwelling plants and animals in places like northern Norway and the Kola Peninsula in Russia, including the predation on capelin eggs.

“Examining jointly both scenarios of focus reveals that competition from red king crabs, with associated increased predation pressure on capelin larvae, could further reinforce a decreasing trend in fish stocks from a shift in Calanus species,” the authors explain. Thus the two main scenarios in the study also interact in ways that are complex and policy relevant.

Food chain and climate change interactions in an Arctic marine ecosystem. From Crépin, et.al 2017. Ambio 46 (Suppl 3): 475.

Highlighting non-obvious links

The authors also emphasize that the Arctic Ocean needs to be put in a global economic and governance context. One example discussed is how climate change impacts in other parts of the world, e.g. decreasing fish stocks combined with crop failures, might lead to incentives to fish more in the Arctic.

Future extensions of the suggested IEBM framework, the authors write, could be to go from qualitative assessments to also quantify the impacts of each scenario on the whole Arctic Ocean social-ecological system.

“The information provided in our framework could facilitate such an exercise by highlighting non-obvious dynamic social, economic, and ecological links that need to be included,” they add.

Another next step could be to develop a user-friendly interface to test different management strategies and their performance against particular objectives.