hey came frightened. They came with broken hope. They came tired and dirty. They came not knowing if they were going back home or not. They came not knowing if they were in the right place. They came with wondrous curiosity. They came with great gratitude.

Joe Teemotee

One such young person was Joe Teemotee. Joe says he was about seven or eight years old when he arrived at Mountain Sanatorium in 1958. He had tuberculosis. He came with two other Inuit who were much older than him, Aulaqiaq and Akumalik. They were from the High Arctic and Joe came from Iqaluit, Frobisher Bay at the time.

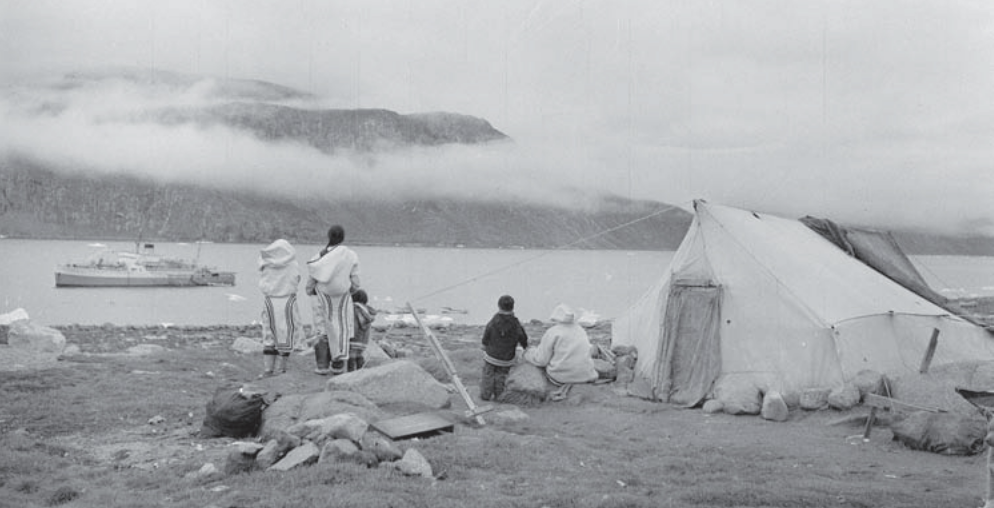

In the 1950s and ’60s the C.D. Howe hospital ship made her rounds in every Arctic community along the coasts of the eastern Arctic each summer. We were still living on the land full-time. The only time we went to the settlements was at Christmas, ship time and to get staple supplies like tea, flour, baking powder, salt, sugar, ammunition, tobacco and jam.

There is an island where people gathered to wait for the supply ships and the hospital ship outside of Kimmirut, Lake Harbour at the time. Supply ships are simply ships delivering goods for the year: building materials, food, mail, cloth materials, fuel and coal. When the C.D. Howe was spotted, we headed for Kimmirut. We were very obedient towards getting medical check-ups since the RCMP members told our people it was necessary for our health. The adults feared the medical check-ups just in case they had sickness and would have to go somewhere south and not come back. To us kids the arrival of a ship of any kind was a time of great excitement and adventure.

It was a time to see so many other people all at once. The adults could hear news of their relatives who were living in different villages along the coast. We saw adults crying because their relatives or friends had died during the winter. They could hear who had babies or who got married. When we lived on the land our villages were small, usually three to five families.

During the medical check-ups, our entire bodies were checked including our teeth. We had to strip all of our clothing, completely and utterly naked. The hospital ship was called ‘Matavik’ in Inuktitut, simply meaning ‘where you strip.’

Once you were diagnosed with TB or some other illness, you didn’t leave the ship, only your family. I remember anxious moments. We always looked for a nurse or a doctor telling us to stay on the ship. I remember there wasn’t much conversation or laughter while we waited for our turn to be

stripped. Everything was hushed.

Joe Teemotee was a little boy in 1958 when he and his family heard the bad news. He was to leave right away by an airplane, a DC-3, otherwise if he left on the C.D. Howe, the trip would take over three months. The airplane ride took only days.

Joe remembers being very excited the whole time. This was so different from the dog teams his father had. Everything was so fast. Joe, Aulaqiaq and Akumalik travelled together, although they were all from different places: an elder Akumalik was from Pond Inlet, Aulaqiaq from Broughton Island and Joe from Iqaluit.

The plane landed the next day, Joe says: “I think we landed in Moose Factory, Ontario. An Anglican minister met them and it was very comforting because by that time we were overwhelmed by so many foreign things, like food, travel, scenery and the language. None of us spoke any English and we had no interpreter.” The young Teemotee felt sorry for the elder Aulaqiaq who was visibly very ill. He could not walk very fast and was coughing a lot.

Once again, the three Inuit were to experience another kind of travel, a train. None of them had ever seen a train, let alone ridden one. Joe was beyond disbelief while the two older companions looked frightened and anxious. Joe remembers the man who took them to the train yelling at Aulaqiaq for being so slow. He wanted to tell the ma “Aulaqiaq is too sick,” but he could not speak the man’s language. Today Joe says: “I have since learned that trains run on schedule and he didn’t want us to miss the train.”

The train ride was even more exciting than the airplane. Joe didn’t sleep at all because there was so much to see. The trees, houses, green fields, villages, animals, cars, people, and more trees passed by all too quickly for young Joe. He wanted to completely absorb everything because there was so much to tell his family and friends back home.

They finally arrived to their destination but they didn’t know it. They thought they were going to travel some more; instead they were quarantined in a room. They were all together, then separated many days later. Joe never saw Aulaqiaq and Akumalik again.

Inuit await medical examination aboard the CGS C.D. Howe at Coral Harbour, N.W.T. (now Nunavut) in July 1951. The ship came to help, offering medical treatment for Canada's Inuit. But those diagnosed with tuberculosis were kept on board and brought to sanatoriums in southern Canada, where many were forced to stay for a year or two. Hundreds also died away from their home communities. (Wilfrid Doucette/National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada)

Annie Kimalu Palluq

Annie Kimalu Palluq is in her late 70s today. She was a young lady in 1958 when she was x-rayed for tuberculosis and was told she had to go to a hospital in the south. According to Annie, there were many Inuit in the hospital ship. They stopped at every community. The last stop was Cape Dorset where a mother and daughter got on. They had TB. Annie says she remembers laying wide-awake at night listening to many coughs.

The hospital ship docked in the middle of the night in Montreal. The Inuit were gathered and put in the train. Annie looked after two little girls, Sataa and Leevee. The little girls were frightened by the speed of the train and its loud horn. Annie did her best to comfort them, after all they had left their comfort and security behind — their mother and father.

Annie and her sister-in-law Oleepeeka were grateful to be reunited with their relatives and friends when they arrived at the Hamilton Mountain Sanatorium. Annie says: “It was so good to see Kakik and Joanasie Salomonie, my cousins. Kakik used to save me apples and oranges from his meals.”

Often there were no interpreters. Annie Kimalu is grateful to Mary Panigusiq who was one of the main translators/ interpreters for the many Inuit. She wasn’t available all the time; she was so much in demand, not only for the hospitals but for the Federal Government as well. When Mary was available, Annie says, “It was good to learn what was wrong and to know what the medicine was for.”

One of the happy memories Annie has is when she and other Inuit became friends, even though they were from different parts of the Arctic. One new friend she remembers the most is Qalik. Qalik had a very sad story to tell. Her husband was out on the land hunting for the family for several days. Qalik went for the annual medical check-up and was told not to get off the ship because she had TB. The hospital ship sailed away before her husband returned, so her husband never knew where she went. He got home to an empty tent, no wife. The husband wrote and the letter finally found Qalik a year later. When Qalik finally received the letter, she wept and wept until she was exhausted.

When Annie thinks back to her times in Hamilton, she wonders how she and the other Inuit, who didn’t speak a word of English never got lost on the way to the hospital or on the way back home. There were no interpreters or escorts. “If I weren’t taken to Hamilton hospital, I’d be dead,” Nataq declares with conviction, then explains, “when I was in the hospital in Hamilton I got another sickness other than the TB and had to be operated on.” She had appendicitis.

Eemeelayo Annie Nataq

Eemeelayo went to the southern hospitals three different times. The first time was to Hamilton with her mother Akiruq when she was a teenager. They both had tuberculosis. Her TB was so bad that she had to go by an airplane with her mother, Ullak and Evie. They were living outside of Kimmirut on the land. They were picked up by a military plane that had no seats. They landed in Goose Bay, Labrador. It was the very first time Eemeelayo and her companions had been away from their village; the new scenery diverted their thoughts from their illnesses. She remembers seeing trees only in magazines and now here they were in reality.

“We had no escorts or interpreters, only the people who met us when we landed. We had to demonstrate by our hands to communicate. We were very brave and able,” states Eemeelayo. She remembers thinking how good the people were to meet them and make sure they got on the right plane or train. Her voice trails off with “we didn’t get lost. We were very obedient and trusting.”

Eemeelayo describes her bedridden days with pain and humour. She had to be completely in bed, no touching the floor even when her bed was being made or she had to eliminate bodily fluids. The only time she was allowed to sit up was during the meal times. During these long bedridden months, she entertained herself with thoughts about her home, way up North. She played these thoughts over and over.

One day, a new person came to her bedside. There was a silent stare by both of them. The woman was very pretty, well dressed and she carried something in her hand. She opened the item and began to say words, words that were foreign to Eemeelayo. The woman motioned for Eemeelayo to repeat after her. The first word to repeat was “Saa-lee.” When Eemeelayo finally said the word, the woman smiled and nodded her head, so the very first English word coming out of her mouth was “Sally.”

The teacher and student were doing well until Eemeelayo looked around the room. “There was one person looking at me. I froze,” Eemeelayo exclaims. She went on to explain that she has always been very shy. The woman continued to say more words but Eemeelayo would not say anymore; she was too frozen and embarrassed. The woman began to look angry and walked out. She never came back.

The bedridden and medication regiments went on for several months, until one day she was motioned to get off the bed. “I was so eager to get off the bed, to touch the cool floor, to stand up. When my feet touched the floor, I stood up. Then I collapsed! There were no more muscles or fat in my legs,” Eemeelayo remembers. She says she had to learn to stand up and walk all over again. Despite all the pain and despair this brought, Eemeelayo looked forward to the exercise each day because she knew she was on the way to recovery.

Eemeelayo did recover and was sent home, but not for very long. While at home, on the land, she recognized the symptoms of TB. She knew she would have to leave home once again, back to Hamilton. The treatments were gentler and the hospital stay was much shorter. She was once again sent home. The third time the TB came back, she was sent to a different hospital outside of Toronto. The stay was even shorter than the last one. Eemeelayo knows the medication and treatments for TB and other illnesses have greatly improved over the years.

“I became active in health and social services in my community because I wanted to make sure health services were adequate and relevant to our people,” declared Eemeelayo. She served on the Baffin Health Board for several years and indeed helped to improve the health services by instituting proper interpreter/translators, escorts for the elders and proper communications. Years ago, letters took over a year to reach loved ones and today we are just a phone call away.

Sadly, many Inuit didn’t come back home; they are buried at Woodland Cemetery, my mother Josie included. There are Inuit buried across Canada. Their loved ones are still looking for them. Some Inuit died en route to the hospitals. Fortunately, so many more Inuit were cured and came back home and are able to tell their stories, such as the three recounts here.

“Our ability to wait and be patient pays off” is echoed by many Inuit who had to go far away for medical treatment. Many of us believe that if we weren’t treated for TB in southern hospitals there would be a lot fewer Inuit. TB was so rampant, contagious and we had no way to treat it up North, so our gratitude is huge.

Ann Meekitjuk Hanson was born in Qakutut, Northwest Territories in 1964. She has worked as a journalist, broadcaster, philanthropist and was the third commissioner of Nunavut between 2005 and 2010. Hanson has spent much of her professional life in the public sector service, furthering the development of Nunavut and its people through her media and philanthropic work.

This article was originally published by Above & Beyond.