Héloïse Frouin-Mouy, a bio-acoustician and marine mammalogist at JASCO Applied Sciences, is using new techniques to better understand the biology and population of hooded seals through their underwater calls. She was recently able to collect and characterize the underwater vocal repertoire of hooded seals, creating a benchmark for the acoustics community.

Hooded seals are found in the cold waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. They are named for the elastic nose or hood found on adult males. The hood, when relaxed lays like a sack on the front of the face and on top of their head. However, the elastic septum inflates and deflates to resemble a red colored balloon when making in-air calls.

While the in-air vocalizations of hooded seals have been documented in previous publications, very little is known about their underwater vocalizations. Frouin-Mouy, in partnership with Department of Fisheries and Oceans, has made advancements in collecting and characterizing the underwater vocal repertoire of hooded seals. She plans on using this new data to determine the acoustic presence and migratory pattern of this species.

Héloïse Frouin-Mouy recording the sounds of a male hooded seal. Photo: Harrison Macrae

Q: What information does underwater acoustic monitoring allow you to collect?

A: We use the passive acoustic monitoring to better understand when, where and how the marine mammals use some specific areas. So, finding vocalizations in our data set allows us to understand when and why they are at a specific location (breeding or foraging).

Q: What have you discovered about hooded seals using these methods?

A: Studying hooded seals is difficult. They are far from shore and they breed on unstable pack ice during a short period of time. So, it can be hard and dangerous for us to access these remote areas. To date, only two studies have been published on acoustic communication by hooded seals. One in 1973 and the other one in 1995. Both of them were focusing on the in air-sounds. The underwater vocal repertoire for hooded seals is poorly known, and my findings actually suggest that the species has a large and diverse underwater vocal repertoire.

Q: Why do you think there has been a lack of research focused on underwater sounds?

A: I wouldn't say there is a lack of research overall, to date some specific species are still poorly known. The acoustic repertoire of some species has been well studied, such as the harbour seal, which is the most common of all the temperate-water seals. The acoustic repertoire of arctic seals is less known and it's notably due to the difficulty to access the animals in the wild and trying to record their sounds in close proximity. You need to be sure that the sounds that you have in your data set are actually from this species.

In the hooded seal case, the difficulty is because the lactation period and the breeding period are short. The lactation period lasts only 4 days, which is the shortest one in mammals. The animals stay on the pack ice for a short period of time. Trying to find a good window of time to go on the pack-ice to record the animals is pretty difficult due to the weather condition and ice condition (suitable landing site for the helicopter). I was lucky in 2018 that we had the opportunity to do it.

Lactating female hooded seal. Photo: Héloïse Frouin-Mouy

Q: So how do you access them?

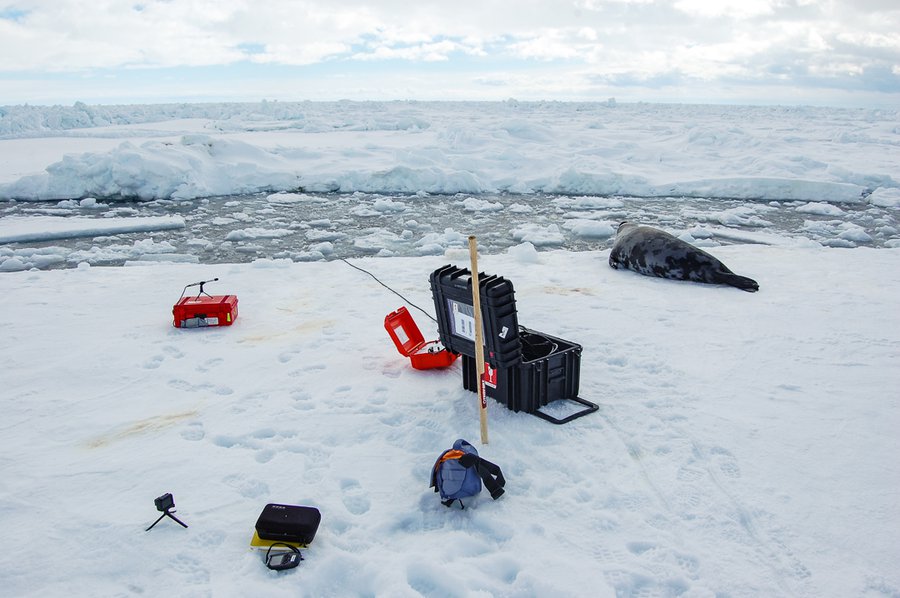

A: For the hooded seals we go into the field using a helicopter because this species breeds on the pack-ice. We cannot have access to them using a boat which we normally use to approach marine mammals. Using the helicopter, we land near the animals and I can install my instruments, the microphone near to the animals and I dig a hole in the ice or use the edge of the ice to deploy the hydrophone (underwater microphone) in the water.

Q: So, when you are listening to the underwater sounds what indicates the population size?

A: My first objective was to characterize the underwater vocal repertoire of this species. But the interesting fact is that when I started to take a look back to other acoustic data sets that we have collected in the past few years in Canada, I actually found some sounds similar to the hooded seal repertoire that I had just characterized. Listening those sounds and looking at their acoustic parameters, I actually realized that they were produced by hooded seals. The exciting fact is that identifying some hooded seal sounds in data from passive acoustic monitoring can become a viable method for investigating acoustic behaviour, as well as studying migratory behaviour of hooded seals. By using those sounds, we are going to be able to monitor for the distribution of population because we will be able to look for those sounds in a large data set of underwater recordings collected along the eastern coast of Canada that we currently have.

Before being able to estimate population size, we will need to more research. Density estimation based on passive acoustic data is still in its infancy.

Q: So, this data has helped to develop a baseline?

Definitely. It's going to be useful for most of the researchers that work with Arctic acoustics. Researchers from several countries where hooded seals are found have already contacted me to figure if some of the sounds that they found in their data sets could be produced by hooded seals. The underwater acoustic repertoire of this species would help to understand the distribution of the species. Knowledge of seal movements is essential, not only for understanding the basic ecology of hooded seals, but for implementing accurate conservation and management programs for this species.

Male hooded seals lay near the edge of the ice. The hydrophone in the water showing spectrogram of recorded sounds - males near to the edge

Q: How is this helping to determine the effect of human-made noise?

Marine mammals, notably in the Arctic, are exposed to increasing anthropogenic noise which includes ship noise. Anthropogenic noise has the ability to interfere with the way in which marine mammals communicate. This phenomenon is termed masking. A way to estimate this masking is to characterize the vocal repertoire of a species to better estimate the frequency range that the animals use to communicate. However, more studies are required to better quantity the impacts of anthropogenic noise on marine mammals.

Q: How have these methods changed how hooded seals are studied?

A: The new perspective is how, by using underwater acoustics, we are now going to be able to monitor the population and understand where they go, when, and which habitats are important for them.

Until now the information on hooded seal distribution are provided by shore-based observation, capture of branded or tagged individuals, vessel surveys, aerial surveys and satellite tag tracking methods. It's a very useful dataset, but it's limited. Acoustic monitoring is less suited than tagging studies for tracking individual animals but it can sample larger fractions of populations to obtain temporal distributions of habitat use at selected locations

Equipment on the ice including a microphone, hydrophone and video camera. Photo: Héloïse Frouin-Mouy

Q: What other data are you hoping to apply the underwater vocal repertoire to?

A: Based on that we currently know of other Arctic seals, it seems that only males produce underwater acoustic display to attract females, to compete with other males or to keep their territory. For now, it seems that only male hooded seals produce the underwater sounds, so the passive acoustic monitoring would provide the information for where the males are. However, females may produce underwater sounds as well. It would be interesting to know if both males and females are producing underwater sounds and to characterize the behavioural context of vocalizations.

Q: How will you be able to do that?

A: A way to do it would be to attach some acoustic tags on female hooded seals so that we can figure out if the females are producing underwater sounds as well and the behavioural context. Unfortunately, I didn't have any acoustic tags during this fieldwork.

Q: Last question, why were you drawn to study these seals specifically?

A: Before working in bio-acoustics I did a PhD in toxicology. I was studying the impact of contaminants on several seal species. I always found seals very interesting because they are curious, and you can closely study them. Later, when I was working in acoustics, I realized that the vocal repertoire and acoustic behaviour, in general, is poorly understood for some of the Arctic seal species. I decided to specialize in Arctic seals so I could help improving this knowledge gap.

Hooded seal pup. Photo: Héloïse Frouin-Mouy