Across Canada’s northern territories, access to services and resources is notoriously limited. Necessities like food and medical care are often in short supply, with the majority of food requiring expensive shipment or delivery to northern communities via air, ice roads, or ships. While various factors influence resource instability, high transportation costs, combined with the region's sheer remoteness and extreme weather, create significant barriers to accessing critical services. And veterinary care is no exception.

To date, there are no permanent veterinarians in Nunavut, and in the Northwest Territories, there are only three veterinarians, all of whom are based in Yellowknife. This means that for animals living in remote areas, urgently needed veterinary care is often a plane ride away.

This veterinary professional shortage is being felt nationwide. According to the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA), hundreds of veterinary jobs will be left unfilled by 2031, a decline that could only exasperate ongoing veterinary challenges already facing Arctic residents and animals.

VWB's Dr. Michelle Tuma examines a Gjoa Haven dog, Boy, as part of VWB_s wellness program. (Credit: Veterinarians Without Borders)

To help address this shortage in the North, Veterinarians Without Borders North America (VWB), an Ottawa-based non-profit dedicated to providing accessible veterinary care and services in more than 13 countries, recently visited the community of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut—the only permanent settlement on King William Island located in the heart of the Northwest Passage. In this community of approximately 1,110, dogs have played a vital role in hunting and transportation for generations.

“Traditionally… dogs were the only source of transportation for the Inuit,” said Gjoa Haven Mayor Raymond Quqshuun Sr. “It was very important for Inuit to have healthy, strong dog teams, and they looked after them very well.” He noted that many of these dogs—primarily huskies—were very well adapted to the North’s extreme cold.

Although there are fewer dog teams in Gjoa Haven today, dogs continue to be an integral part of the community.

“Living in the community with dogs… we need a place for them to be checked by veterinarians,” Quqshuun Sr. said. “This will become more important in the future as the community grows.” He also emphasized the connection between veterinary care and maintaining the health of both animals and humans.

Romi Lotoski & CAHW trainee, Jimmy Pauloosie Jr., examine a dog at the VWB wellness clinic. (Credit: Veterinarians Without Borders)

VWB’s recent visit to Gjoa Haven was in direct response to this need through the launch of their very first northern Community Animal Health Worker (CAHW) training program, funded by PetSmart Charities of Canada. The trip also included a veterinary wellness clinic and a community meeting, attended by over 40 community members and a translator, to discuss local animal health concerns. VWB has been visiting the community on an invite-only basis since 2022, providing temporary veterinary clinics that offer vaccinations, spays and neuters, and general checkups.

“VWB already had CAHW programs associated with our international programs,” said Dr. Michelle Tuma (DVM), VWB’s northern veterinary specialist who is based in Yellowknife, NWT. “We considered how we could utilize that model and tailor it to the unique needs and characteristics of the North,” she added, also noting that CAHW programs “really help strengthen local capacity [by] empowering community members to care for their own dogs and animals.”

In Gjoa Haven, the CAHW training took place over two days in partnership with two community members—Bylaw Officer Jimmy Pauloosie Jr. and Community Safety Liaison Sam Tutanuak. A member of the Arctic Response team, Zach Renholder, who works closely with the Hamlet for program implementation, also participated in the session. It was led by Tuma along with Registered Veterinary Technologist, Romi Lotoski. Both Tuma and Lotoski trained participants in animal health and welfare, including dog behaviour and handling, recognizing signs of distress and disease in dogs (such as rabies), administering subcutaneous injections (including vaccinations), and humane euthanasia and ethics. Once trained, CAHWs can respond to local animal health concerns, which include administering vaccinations to animals using a supply that VWB leaves behind or can ship to the community as needed.

Jimmy Pauloosie Jr. (R) demonstrates how to administer a vaccination to OVC MSc student, Hannah (Tsai-Ping) Liao (L). (Credit: Veterinarians Without Borders)

Tutanuak noted that, as part of the training, learning about ways to approach and handle dogs was particularly beneficial. He added that “the remote location [of Gjoa Haven] and unavailability of veterinarians during emergencies” are two important factors that contribute to the need for increased access to veterinary care.

Tuma also emphasized how difficult it can be to access care in Nunavut.

“There are 25 communities in Nunavut that are only accessible via plane, so the remote nature and the territory’s unique landscape create a lot of barriers to accessing veterinary services,” said Tuma. “If a pet guardian did want their animal to be seen by a veterinary professional, they would have to fly their animal thousands of kilometres to Yellowknife, or another larger city out of territory, to get into a clinic, which is costly and can also be very scary and stressful for the animal,” she added.

Romi Lotoski, RVT, holds a dog as Dr. Michelle Tuma guides CAHW trainee, Jimmy Pauloosie Jr. in vaccinating. (Credit: Veterinarians Without Borders)

Accessing veterinary care isn’t just about helping animals; it’s also about preventing the spread of deadly zoonotic diseases, like rabies, which is endemic in arctic foxes. While fox populations naturally ebb and flow, largely dependent on access to food sources, climate change could increase the frequency of fox visits to communities due to a decline in sea ice and their ability to travel and find food. Once in town, rabid foxes are more likely to encounter community dogs, increasing the risk of transmission to other dogs and nearby residents. Fortunately, vaccinations can help prevent the development of rabies, even if dogs are exposed to the virus.

Pauloosie Jr., one of the CAHW trainees, learned how to administer vaccinations and helped inoculate dogs during a wellness clinic hosted by VWB during their visit. “I enjoyed learning to give out vaccinations, and I’d like to keep going so I can gain more experience with the organization,” he said.

VWB hopes to continue training local community members across the North, including other Arctic communities.

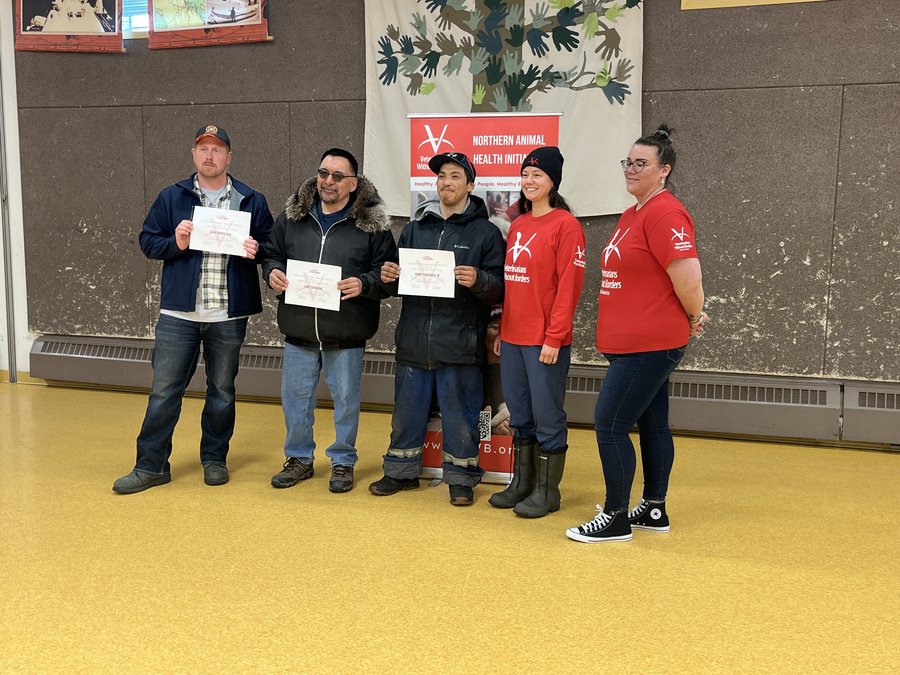

VWB trainees present CAHW with certificates of completion (L-R), Zach Renholder, Sam Tutanuak, Jimmy Pauloosie Jr., Michelle Tuma, Romi Lotoski. (Credit: Veterinarians Without Borders)

As for the future of animal health care in Gjoa Haven? Increased governmental support and encouraging young people to pursue animal health care training across the North and Arctic may hold the key to seeking long-term solutions to accessing veterinary care. This includes not only funding and resources, but also the recognition that animal health is deeply connected to community health and well-being.

“There are currently no governmental departments in the North that take responsibility for domestic animals,” said Tuma, noting that other governments in Canada, such as in Manitoba and Ontario, do assist. “Helping communities with these types of concerns and challenges would be really amazing,” she said.

The gap in services leaves many communities relying on visiting veterinary teams or volunteer programs to meet basic animal health needs. Local capacity strengthening, including training Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs), plays a crucial role in bridging this gap, especially in scenarios where outside help may not be readily available.

“In the future, I’d like to see young people take up training in college or university to become veterinary professionals in the community… that’s the dream,” said Quqshuun Sr.

His hope reflects a growing interest in creating sustainable, community-led approaches to animal care in the North; solutions that are rooted in local knowledge and long-term investment.