University of Manitoba graduate student discovered Canada’s first, genuine, scientifically sound monster lurking under our Arctic sea ice.

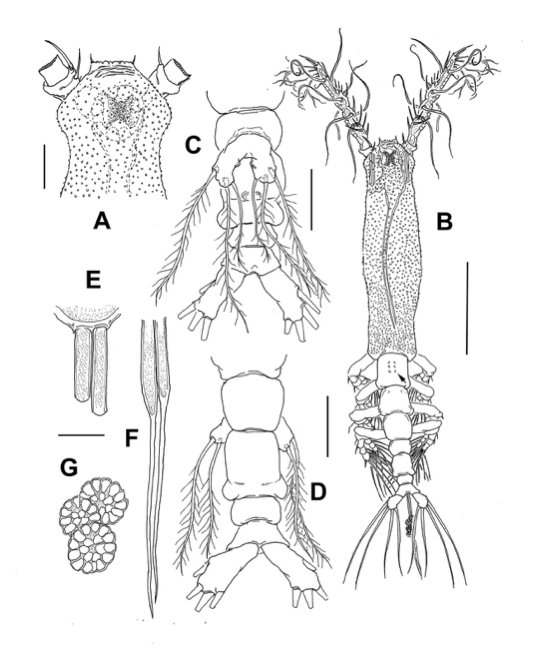

In adult form, the beast uses eight bristly legs to paddle its mostly translucent body through the dark water. It has one weak eye, no mouth, and two antennas adorned with ragged, flowing hairs. Thankfully, for sleep’s sake, it is only 2mm long.

Aurelie Delaforge did not purposefully seek this monster out in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. But she found it, and now Canada’s arctic biodiversity includes a new copepod of the Monstrilloida family, derived from the word “monster”. There are more than 160 different Monstrilloida zooplankton floating around the oceans, and now Canada’s Arctic has a species of its own.

This discovery came thanks to two noteworthy coincidences. One, Delaforge studied the taxonomy of small ocean animals and plants for her masters back home in France and so knew enough to recognize the oddity. Two, while living on an ice camp in Canada’s high arctic, she was sampling the ocean to support her PhD thesis on what causes plankton blooms under the sea ice, and she took the samples during the short two-month window these animals take adult form—May and June. Outside of these months, the animal would be nearly invisible as larvae or busy living as a parasite inside animals like clams and sponges. But by luck, the creature kept showing up in her samples, suggesting it didn’t just drift over from somewhere else. It was local.

Alien!

After returning to her lab at the U of M, Delaforge sent a text to a Department of Fisheries and Oceans researcher, Wojciech Walkusz: “I have this alien!!!” He immediately suspected it was a Monstrilloida so she sent her specimen to Mexico where the world’s foremost monster identification specialist resides. Eduardo Suárez-Morales dissected the tiny creature and confirmed the Canadian Arctic’s first, true monster: Monstrillopsis planifrons, or flat headed monster.

Delaforge and her colleagues published their discovery, “A new species of Monstrillopsis (Copepoda, Monstrilloida) from the lower Northwest Passage of the Canadian Arctic”, in the latest edition of the ZooKeys journal.

“When we study the Arctic, there are still things we don’t know. This is a good example,” Delaforge says. “I find this pretty cool. It’s not an everyday thing, discovering new species and it feels incredible. I wasn’t looking to find a new species for my PhD, but for me personally, who loves taxonomy, I think this is really important because it brings new information on the biodiversity present in the Arctic. It’s important to know what’s there.”

Monstrillopsis planifrons sp. n., adult female holotype from the Canadian Arctic. A cephalic region, dorsal view B habitus, dorsal view C urosome, ventral view, showing fifth legs D urosome, dorsal view E insertion of ovigerous spine on dorsal surface of genital double-somite F terminal section of ovigerous spines G eggs along ovigerous spines. Scale bars: A, C, D 100 µm, B 500 µm, E–G 25 µm. // Drawing from ZooKeys paper: “A new species of Monstrillopsis (Copepoda, Monstrilloida) from the lower Northwest Passage of the Canadian Arctic”

This article was originally published by UM Today.